Drone

A short reflection on noise

“We cannot keep our ears closed or sounds out.”

Can you hear the birds? Their song is masked by the drones of the city.

Drone: the Israeli military drone.

Drone: the low humming sound of the generators populating my neighborhood.

Drone: the continuous whir of the battery that powers our apartment when all other sources of electricity (government, generator, solar) fail us.

These noises serve a clear function and purpose. Noises are information. Noises talk to us. They drone, on and on. They are telling us something.

This process of interpreting sound is what anthropologists might call “agile listening” – whereby our ears “listen to the multiple layers of meaning potentially embedded in the same sound” (Masri, 43). Sensory anthropologists like Sarah Pink encourage ethnographers to take note of such sounds and other embodied experiences during fieldwork, asking themselves: What is it I am hearing? What does it tell me about the space? How is it heard by and interpreted by myself and others? What feelings does it evoke in me and in others and why? (Masri, 43).

This is because anthropologists and social theorists in general (like Adorno, for instance) maintain that sounds are inherently embedded with cultural and personal meanings. In other words, “sounds do not come at us raw” (Masri, 42).

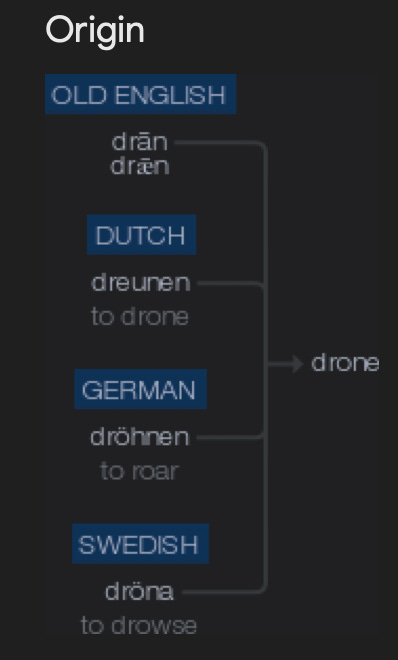

Drone: Old English drān, drǣn ‘male bee’ …

The Israeli drone sounds like an army of angry hornets. As I write this, sitting on my sofa on this otherwise quiet Sunday morning, I can hear it come alive again. Wait, no – that’s not the drone. It’s the sound of construction, someone is drilling something. Or is it?

Our ears deceive us. We often mistake some sounds for others, drawing on sonic information we’ve stored from years past. Sometimes, noises lie to us. They feed into our delusions and recall memories we hold in our bodies that scare us. This is what Toni Morrison called rememory in her novel Beloved: remembering something that one had forgotten one knew.

“The past comes to us in the most unbidden, immediate, and sensuous forms,” writes Fran Tonkiss. Sound has a very particular relationship to memory. When we have auditory experiences, we imbue them with meanings (whether we are aware of it or not) which then come to hold a place in our auditory memory, influencing our future experiences of sound.

Drone: from a West Germanic verb meaning ‘resound, boom’ …

I am watching TV with my friend, and suddenly we hear loud bangs. I panic, reflexively reaching for my phone. Fireworks or gunfire?

These bangs, too, are information: Is it a private achievement or a political victory that is being celebrated? An assassination? The beginnings of a sectarian skirmish? Or is someone getting shot after a personal disagreement?

One night in 2021, I stayed up until 2 AM watching TV and then heard the unmistakable sounds of gunfire from the street below my house. I hid behind a wall, paralyzed, wondering if I should wake my family up. The next morning, it was like nothing happened.

Drone: related to Dutch dreunen ‘to drone’, …

I hear the drone of the small flying military aircraft and it tells me that war is nearby. We are not safe. I hear the drone of the battery inverter and it speaks to me: it tells me that it is overheating. I hear the drone of the fan in the battery room: it makes an uncomfortable noise, swiveling in a vain attempt to cool the battery down. I hear a drone from the kitchen balcony: the drone of the neighborhood’s generators, feeding homes with electricity. This drone means we can rarely open the windows; when we do, black soot covers the furniture and the smell of exhaust makes us choke. I can hear the drone of traffic, too, and it tells me that it is rush hour: people honking horns in frustration, the everyday regularity of Hamra traffic.

Drone: German dröhnen ‘to roar’, and Swedish dröna ‘to drowse’.

We live among machines and their droning. It sounds like a gang of stinging bees, like a roar of exhaustion, and like a faint, yet always present, buzz.

Sources

Malmström, Maria. (2021). “The Desire to Disappear in Order Not to Disappear: Cairene Ex-Prisoners after the 25 January Revolution.” The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology. 39. 96-111. 10.3167/cja.2021.390207.

Muzna Al-Masri (2017). “Sensory reverberations: rethinking the temporal and experiential boundaries of war ethnography,” Contemporary Levant, 2:1, 37-48, DOI: 10.1080/20581831.2017.1322206

Tonkiss, Fran. 2003. “Aural Postcards: Sound, Memory and the City.” In The Auditory Culture Reader, edited by Michael Bull and Les Back, 303–310. Oxford: Berg